From Year to Year, from Decade to Decade, from Century to Century, and from Trump and Netanyahu to Blair. Image produced by artificial intelligence.

The spectre of Balfour will continue to hover above our heads like the sword of Damocles — to kill us, expel us, and divide our lands.

By Dr Noha Khalaf, from Paris

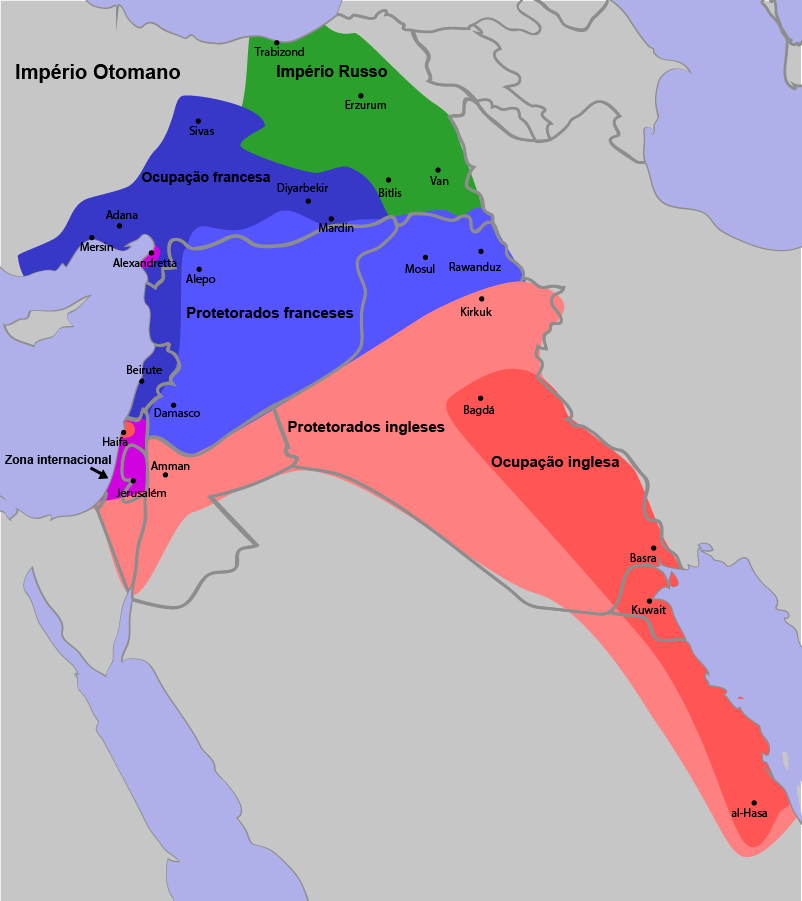

In 1917, it seemed that the world’s political stage had been set for the drafting of the Balfour Declaration, for the international Zionist movement had already organised itself and had been planning the creation of a homeland for the Jews for more than twenty years, since the First Zionist Congress held in Basel in 1897. Meanwhile, the fate of the Middle East lay in the hands of the victorious European powers — particularly France and Great Britain — which divided the remains of the Ottoman Empire and began the formal partition of these lands in 1916 through the Sykes–Picot Agreement. After the First World War and the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire, the year 1917 (when the Balfour Declaration was drafted) may be considered a pivotal moment in the history of the modern Middle East.

The historian David Fromkin, in his book A Peace to End All Peace, noted that the period between 1914 and 1922 was the historical interval that shaped the contemporary Middle East. Similarly, the French historian Nadine Picaudou, a specialist in Middle Eastern history, considered the years 1913 to 1924 as the decade that “shook” the structure of the region.

According to the Hussein–McMahon correspondence, France appointed Georges Picot and Britain appointed Mark Sykes to draw the final lines of their respective spheres of influence in the Middle East as early as 1915. Their proposals were then submitted to the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Grey, and to the French Ambassador in London, Paul Cambon, and subsequently referred to Russia for approval.

As is well known, the Sykes–Picot Agreement established three zones: the “Zone A”, in blue, under French influence (a mandate within the proposed Arab state); the “Zone B”, in red, under British influence; and a third zone, in brown, which included Palestine. The agreement specified that “Palestine shall be placed under an international administration, the form of which is to be decided upon after consultation between Great Britain, France, and Russia, and subsequently in consultation with the other Allies and the Sharif of Mecca”.

It is clear that this agreement represented, for the Zionist movement, a golden opportunity to begin implementing its project to create a Jewish state in Palestine, which led to intense political consultations culminating in the drafting of the Balfour Declaration.

The British journalist Joseph Jeffries shed important light on the document in his 1939 analysis. He defined the Balfour Declaration as a proclamation “in which every word was carefully weighed”, despite containing only 67 words. According to his analysis, each of these words was scrutinised before being included in the text. Several preliminary drafts circulated between Britain and the United States, with more than a dozen advisers participating in their revision. Jeffries summarised: “There is no other communiqué whose preparation took longer, whose issue was more precise, and whose wording was more consciously elaborated than this one.”

He cites Nahum Sokolow, in A History of Zionism: “Every idea conceived in London was examined by the Zionist Organisation in America, and every American proposal received special attention in London.” Rabbi Wise, who took part in the consultations, admitted that the Balfour Declaration “was prepared over a period of two years” and that its drafting “was a collective, not an individual, work.”

Although the text was ready on 2 November 1917, it was only published in the press on 9 November, presented as an exclusively British initiative when, in reality, it was a joint British–Zionist creation. (It is worth noting that the declaration was only made public in Palestine in 1920.)

Frank Manuel, in his book The Realities of American Policy in the Near East (1949), observed that the American Zionist judge Louis Brandeis played a major role in drafting the document. Balfour himself discussed the text with Brandeis during his visit to the United States in May 1917. On 1 September, Chaim Weizmann sent a draft of the document — already approved by Britain — to Brandeis, requesting the approval of both him and President Woodrow Wilson. As there was no written record of Wilson’s consent, Brandeis sent a telegram to Weizmann on 24 September stating that “based on the opinion of President Wilson’s advisers, it is believed that the President views the matter with sympathy.” However, it appears that Wilson later wrote to Colonel House, one of his advisers who had shown him the text: “I regret to say that I never stated that I approved the proposed wording of the other party, and I should be obliged if you would let them know this.”

The September draft, sent by Weizmann, contained the phrase “Palestine should be reconstituted as the national home of the Jewish people”, but it was altered in the final version to “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people”. Manuel therefore concluded that he doubted Balfour was the actual author of the declaration, seeing him rather as the facilitator of its approval.

On 2 November 1917, Lord James Arthur Balfour, the British Foreign Secretary, sent Lord Rothschild, one of the Zionist leaders of the time, the following letter:

“My dear Lord Rothschild,

I have much pleasure in conveying to you, on behalf of His Majesty’s Government, the following declaration of sympathy with Jewish Zionist aspirations which has been submitted to, and approved by, the Cabinet:

‘His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.’

I should be grateful if you would bring this declaration to the knowledge of the Zionist Federation.”

Yours sincerely,

Arthur Balfour.

In Jeffries’s analysis, particular attention is given to the meticulous examination of every term in the declaration. He observed, for example, that the expression “national home” first appeared in lower case letters in its initial publication in The Times, and was later replaced with capital initials in the official text. The term itself was unfamiliar to the British, although it had been used thirty-five years earlier by Leon Pinsker in his 1882 book Auto-Emancipation, without reference to Palestine.

According to Jeffries, it was unclear to the British how the idea of a “national home” was to be applied, and this ambiguity was intentional — allowing each party to interpret it according to its own interests. For the Zionist movement, it was evident that it meant the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine.

Jeffries also showed that expressions such as “view with favour” and “to facilitate the achievement of this object” were vague formulations, open to multiple interpretations. However, he considered the most misleading phrase to be the one referring to the Palestinian Arabs as “the existing non-Jewish communities”, as though they were a minority, when in reality they constituted about 90 per cent of the population, whereas Jews made up barely 9 per cent. This terminological choice was designed from the outset to conceal the true demographic reality.

The most important point highlighted by Jeffries lies in the following passage:

“…nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

In this passage, the word “political”, which should also have qualified the rights of Palestinian Arabs, was deliberately omitted, mentioning only “civil and religious rights” for them, while in relation to the Jews the text explicitly mentions “rights” and “political status” — not only within the future national home but also in other countries.

This detail — the absence of political rights for the Palestinians — laid the foundations for the apartheid system that the Zionist state still applies today across all Palestinian territories (whether within the Green Line or in the West Bank and Gaza). Even more serious is the principle contained in the document that the “political status” of Jews in other countries should not be affected, thereby legitimising the existence of powerful Zionist lobbies throughout the world and allowing Israelis to hold multiple nationalities. Meanwhile, Palestinians, especially refugees, remain doubly stripped of all political rights, both in their original homeland and in the places of exile and diaspora imposed upon them.

Thus, for more than a century, in accordance with the ill-fated Wada‘ Balfour (Balfour Promise), Israelis have been permitted to dominate the world while working to strip Palestinians of all rights and to erase their very existence.

The war of extermination and starvation imposed on the Gaza Strip, as well as the savage offensive against the Palestinian people in the West Bank, are nothing more than the continuation of the implementation of Balfour’s plan and that of his Zionist and American partners.

New geopolitical map of the Middle East according to the Sykes–Picot Agreement.

French occupation.

British (English) occupation.

Russian occupation (Russian Empire on the map).

Zone “A” – location of French protectorates.

Zone “B” – location of British (English) protectorates.

International zones.

Source: Wikipedia.

Text Editing: Alexandre Rocha